Mixins make sense

Posted on by Idorobots

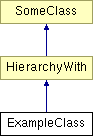

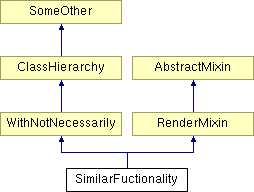

Let's suppose we have this class hierarchy:

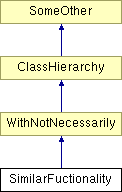

It's a fairly specialized class hierarchy providing some functionality, let's say for the sake of this example that SomeClass provides a kind of player-game interaction interface and HierarchyWith defines it as a trigger based interaction (as in "a player does something - it triggers a response"). Our ExampleClass represents an entity that can be triggered by the player and that generates some response and in addition to that is further specialised to have some concrete functionality - let's say it's a lever that a player determined enough can pull to flood something with delicious magma. As we clearly can see ExampleClass is well-defined in terms of OOP, it's highly specialised and modular, but as an in-game entity it lacks a rather crucial functionality - it can't even be displayed on the screen. What do we do now? Adding a render() method is pretty straightforward, but it's against the modularity principle - ExampleClass' hierarchy is meant to provide player-game interaction and player-game interaction only; by adding a render() method to SomeClass or HierarchyWith class we allow the hierarchy to perform two not related in any way tasks. And what if we wanted some other things rendered as well? Say we have:

Do we add a render() method to this hierarchy as well? We'll end up with two different hierarchies performing two different things each that have the rendering in common. Not going to happen on my watch. We could create an interface, say Renderable, that would allow us to define needed methods wherever we wish to simply by implementing it. This is a slightly better idea, however we still need to implement the interface in various places and sometimes that may lead to awful code duplication and no reuse at all. That doesn't sound like a serious problem, but imagine we needed 10 interfaces implemented in 100 classes that do pretty much same thing in every single one. And some languages don't even have interfaces, yo!

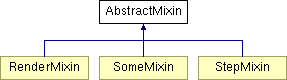

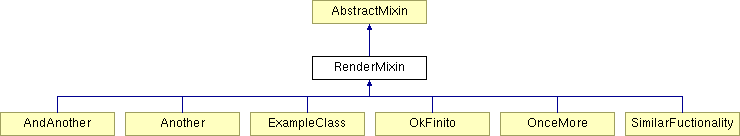

Another way to deal with this is using mixins. A mixin is a construct (not calling it a class on purpose, will goto to this later) that allows us to inject additional code to a class, or mix it in, if you please. One way of implementing mixins is by simply using regular inheritance - all we need is an abstract class (C++, yo) and a handful of derived classes that will inject some code:

And the code:

class AbstractMixin {}; //Let's pretend it's abstract

class RenderMixin : public AbstractMixin { //So is this.

virtual void render() const {

//Does rendering

}

};

class StepMixin : public AbstractMixin { //And this

virtual void step(float dt) {

//Does something

}

};

class SomeMixin : public AbstractMixin {

virtual void anything() {

//Does anything

}

};

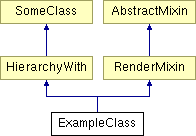

Now we need to simply derive these mixins to inject the code into the derived classes:

And:

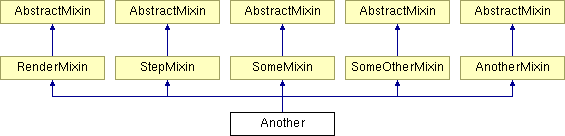

Both our ExampleClass and SimilarFuctionality classes can do the rendering now AND their hierarchies remain pure. We either can override the methods (and thus mixin will act as an interface) or reuse the code it already supplies. We can do so wherever we please:

And as much as we please:

We pretty much can do anything() [sic]. Too bad it requires multiple inheritance because it won't work in Java for example, and we all know that multiple inheritance is nothing to be desired. Speaking of Java... There is a very limited way of implementing mixins using com.javadude.annotations.Bean. We need a couple of interfaces coupled with their implementations and a little trick... Here is the mixin code:

package mixins;

public interface Renderable {

void render();

}

public interface Stepable {

void step(float dt);

}

public interface Someable { //What?

void anything();

}

public class RenderMixin implements Renderable {

void render() {

//Does rendering

}

}

public class StepMixin implements Stepable {

void step(float dt) {

//Does something

}

}

public class SomeMixin implements Someable {

void anything() {

//Does anything

}

}

And here is the great trick I've mentioned a minute ago:

package example;

import mixins.*;

import com.javadude.annotation.Bean;

import com.javadude.annotation.Delegate;

@Bean(delegates = {

@Delegate(type = Renderable.class,

property = "renderMixin",

instantiateAs = RenderMixin.class),

@Delegate(type = Stepable.class,

property = "stepMixin",

instantiateAs = StepMixin.class),

@Delegate(type = Someable.class,

property = "someMixin",

instantiateAs = SomeMixin.class)

}

)

public class ExampleClass

extends ExampleClassGen

implements Renderable, Stepable, Someable

{

//Additional functionality

}

We create a Bean which collects the functionality of the mixins we wish to implement in our class and we derive a class generated in this way, simple. Why is it so limited? Well, first of all we derive a generated class which means we can't use this with any of our own inheritance, but the real deal is inside of the generated class:

// CODE GENERATED BY JAVADUDE BEAN ANNOTATION PROCESSOR // -- DO NOT EDIT - THIS CODE WILL BE REGENERATED! --

package example;

@javax.annotation.Generated(

value = "com.javadude.annotation.processors.BeanAnnotationProcessor",

date = "Thu Apr 7 23:25:48 EDT 2011",

comments = "CODE GENERATED BY JAVADUDE BEAN ANNOTATION PROCESSOR; DO NOT EDIT! THIS CODE WILL BE REGENERATED!")

public abstract class ExampleClassGen {

private mixins.Renderable renderMixin_;

private mixins.Stepable stepMixin_;

private mixins.Someable someMixin_;

public ExampleClassGen() {

;

renderMixin_ = new mixins.RenderMixin();

stepMixin_ = new mixins.StepMixin();

someMixin_ = new mixins.SomeMixin();

}

public void render() {

renderMixin_.render();

}

public void step(float dt) {

stepMixin_.step(dt);

}

public void anything() {

someMixin_.anything();

}

@Override

public java.lang.String toString() {

return getClass().getName() + '[' + paramString() + ']';

}

protected java.lang.String paramString() {

return "";

}

}

It's a composite that redirects method calls to its private fields... Hey, it's Java! It's slow anyway! Summing up what we have so far: we either create lots of nonreusable code or all we get is a really limited functionality and low performance; we're forced to use exotic constructs such as multiple inheritance and whatnot. Long story short: we ask for trouble and we ask ourselves "why even bother?".

In fact that's a good question, why such a simple idea (as simple as a mixin can get) has to be so hardcore pain in the butt when it comes to implementing it? Answer: It doesn't have to. Danna, danna, danna, danna, di dam! (A sound D makes when entering the stage, true story.)

First of all in D mixins are built into the language and that makes them pretty powerful for starters. That's why I didn't call a mixin a class earlier, it doesn't have to be a class at all. Consider the following:

import std.stdio;

int foo = 42;

void main() {

mixin("int foo = 23;");

writeln("foo is ", foo);

}

It writes 23 on the stdout, why? We declare a global integer foo and then mix another one with different value into the scope of the main function, hence it gets written to the stdout. Mixins in D are evaluated at compile time meaning they get compiled into the scope they appear in after they are semantically analysed and since strings are immutable in D, int foo = 23; can be evaluated at compile time and can be added to the scope. It's a rather simple example, we add a string into a scope and that's it, but there's way more to it than that:

mixin template Foo() {

int foo = 23;

void bar(int foobar) {

writeln("bar called with ", foobar);

}

}

void main() {

mixin Foo;

writeln("foo is ", foo);

bar(4);

}

Now we use a template mixin - a kind of a template, that gets compiled into a scope it's called in. Note that it still gets analysed semantically unlike C/C++ preprocessor macros. This time we added a variable foo and a function bar. If we mixed Foo into a class D would compile a bar method into the scope of the class. Why is it more powerful than regular mixin implementations? The reason is simple - no additional performance overhead, the mixin scope is added directly to the scope it appears in, so no virtual calls nor any composites are required. Neither does it interfere with class inheritance.

Template mixins can be parametrized just as regular D templates:

mixin template Foo(T) {

T foo = 23;

void bar(T foobar) {

writeln("bar called with ", foobar);

}

}

void main() {

mixin Foo!double;

writeln("foo is ", foo);

bar(3.14);

}

And they can even use mixins themselves:

mixin template Foo(T, string name) {

mixin("T "~name~" = 23;");

void bar(T foobar) {

writeln("bar called with ", foobar);

}

}

void main() {

mixin Foo!(double, "foo");

writeln("foo is ", foo);

bar(3.14);

}

This is how our earlier example classes could look written in D:

import std.stdio;

mixin template Renderable() {

void render() const {

//Does rendering

}

}

mixin template Stepable() {

void step(float dt) {

//Does something

}

}

mixin template Someable() {

void anything() {

//Does anything

}

}

public class ExampleClass {

public:

mixin Renderable;

mixin Stepable;

mixin Someable;

}

public class SimilarFuctionality {

public:

mixin Renderable;

}

void main() {

auto e = new ExampleClass();

e.render();

e.step(3.14);

e.anything();

auto s = new SimilarFuctionality();

s.render();

}

Note how elegant it is. Needlessly to say "mixins make sense again".

2016-02-20: Adjusted some links & tags.